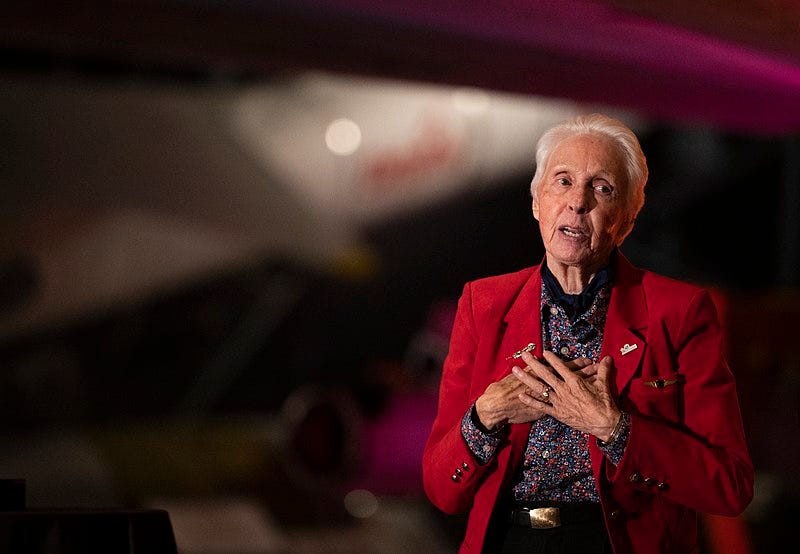

July 20, 2021, is a day forever emblazed in Wally Funk’s memory. After waiting six decades for a chance to go into space, the 82-year-old pilot climbed into a Blue Origin rocket in Van Horn, Texas and blasted off to finally fulfill her dream.

On that day she made history as the oldest person to soar above the Karman line, the boundary that defines true space, about 62 kilometers above earth’s sea level. It didn’t matter that the trip lasted 11 minutes. For Funk, the ride represented mission accomplished for a goal she had been pursuing ever since she was 21 and a member of the Mercury 13, a unique group of women who could have been America’s first female astronauts.

Wally Funk is the only member of the Mercury 13 to go to space.

Funk deserves a place in American history through her connection with two eras in space. Who else can say they were part of of the America’s first space program and today’s era of space travel that runs the gamut from scientific exploration to commercial tourism?

Who were the Mercury 13? Most people know about the Mercury 7, NASA’s original seven astronauts who were the first Americans to go into space in the 1960s. Far less is known about the Mercury 13 or The First Lady Astronaut Trainees (FLATs), a mostly forgotten, short-lived group of extraordinary female aviators.

Some FLATs like Irene Leverton, Gena Nora Stumbough and Jan Dietrich were flight instructors with thousands of hours of experience. One of them, Bernice Steadman, was the owner of a Michigan flight school and charter operation. She had taught hundreds of men how to fly corporate and private planes. Another aviation entrepreneur was Myrtle Cagle who ran her own airport in Selma, Alabama and held an airport transport license.

Others were professional air racers like Rhea Hurrle and Sarah Lee Gorelick, 27, who got her license at 17, began racing at 18 and had won multiple Powder Puff Derbies. Jane Briggs Hart, the oldest FLAT at 41, was a mother of eight children and the first woman to earn a helicopter license in Michigan. The youngest FLAT, Mary Wallace “Wally” Flat was 21 and had the distinction of being the first female flight instructor at a military airbase.

They were a diverse and deeply talented bench of pilots, drawn from all levels of society who shared a passion for flying. In a society that was figuring out the roles of women in a post war era, flying offered freedoms that appealed to them.

From 1960-1961, each woman was handpicked to be part of a privately funded, under the radar testing program that asked the question, “do women have the right stuff to be astronauts?” The answer was “yes” -- women definitely had the “right stuff” in terms of skills and test scores. The only thing “wrong” with them was they weren’t the right sex.

The Cold War era of the late 1950s and ‘60s was a time when social and political change was simmering throughout American culture. The United States and Soviet Union, once allies during World War II were now engaged in a struggle to become the most powerful country in the world.

An unofficial space race was one manifestation of this competition and America’s power, prestige and ambition were on the line. The Soviets were the first to put satellites into orbit, followed by the milestone of the first man into space. Meanwhile, NASA was struggling to figure out why it couldn’t consistently get rockets off the launch pad without the rockets exploding. Finally in May of 1961, the United States could claim success when a rocket called Freedom 7 lifted off carrying Alan Shepherd as the first American into space.

Seizing on this accomplishment, President John F. Kennedy decided to go for the moon, literally. In a famous speech to the nation later that month, Kennedy laid out the priority “to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to earth.”

In his speech Pres. John Kennedy laid out the stakes of the space race. “No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

Shepherd had spent 15 minutes in space and now the United States was going to the moon in less than nine years? This jaw- dropping statement was a stunning declaration of patriotic confidence, the equivalent of throwing down the gauntlet in the space race. Perhaps no one was more surprised than the people at NASA. From May 26,1961- the day after Kennedy’s speech – it was go time on the countdown calendar and anything that interfered with getting to that finish line was out of the question.

It's likely that Kennedy didn’t know anything about the FLATs when he made his speech because the program was not NASA’s idea. Rather, it came from two prominent military doctors who had been hired by NASA to help select the Mercury 7 astronauts.

Dr. William Randolph Lovelace and Air Force Brigadier General Donald Flickinger had evaluated and tested more than 500 candidates - all men – to determine the final seven. Both were pioneers in the new field of aviation medicine. Lovelace was one of the inventors of the oxygen mask that has become part of the emergency kit for passengers on today’s airplanes. Women, however, weren’t among the candidates because NASA wanted only military test pilots and in1958, there were no female test pilots.

The two doctors believed that women had specific advantages over men in space based on anatomy and biology. Lovelace’s thinking was summarized in a 2009 article in the Advances in Physiology Education journal.

“First, there would be a reduction in the propulsion fuel required to send the rocket's load into space, as women were lighter and would require less oxygen than men. Second, women were known to have fewer heart attacks than men; at this time, it was not known how the stress of microgravity would affect the cardiovascular system. Third, the internal reproductive system of the female was thought to be less susceptible to radiation than that of the male. Finally, there were preliminary data available suggesting that women could outperform men in enduring cramped spaces and withstanding prolonged isolation.”

Two years after the Mercury 7 members had been selected, without asking or seeking NASA’s approval or involvement, Lovelace’s decided to turn his New Mexico medical clinic into a testing site for his Women in Space (WIS) program. His plan was to use the same tests the astronauts had been given on women. His first test subject was 29-year-old Geraldyn “Jerrie” Cobb, one of the most accomplished fliers in the country.

Cobb had fallen in love with flying from the time she was a child in Norman, Oklahoma. She took her first lessons on her father’s plane, earning her pilot’s license on her 16th birthday. Flying was her sole passion in life once she finished school. She took a job as a crop duster because that was one of the few outlets available to women pilots. She flew for a commercial ferrying service, delivering planes over the Andes in South America, a job considered too dangerous by many male pilots. In 1959, she was the first woman to fly in the Paris Air show. By 26, she held world aviation records for speed, distance and altitude. In 1960 when she arrived at the WIS program, she had more than 10,000 hours of flight time on her resume – far more than the 1500 hours that NASA required of astronauts.

The tests were designed to be tough. Scientists didn’t have a lot of information about how the human body would react in space so they created a range of stressful situations. Doctors injected 10-degree temperature water into Cobb’s ears to record her reaction to the resulting dizziness and loss of balance. They put her on a stationary bicycle and wouldn’t let her off until her heart rate hit just below 180, the point when humans lose consciousness.

From there the tests got even more rigorous. They suspended her in an isolation tank filled with water, closed the door to the room to block out all light, sound, vibration and smell to see how long she could last. The answer was 9 hours and 40 minutes, surpassing some of the Mercury men.

By far the worst exercise was the MASTIF – a huge space simulator that resembled a nausea inducing amusement park ride. The rig was a gyroscope the size of a two-story house that consisted of three nesting cages that rotated independently. As the test subject sat in the center of the rig, with a hand controller and instrument display, each axis would spin, gaining speed and rotation. The mind-bending motions were intended to replicate a space vehicle spinning out of control and the goal was the “tame” the beast.

Jerrie Cobb in a space simulator called the MASTIF.

According to the report in the Advances in Physiology Education journal, Cobb endured 45 minutes in this gut-wrenching device. Alan Shepherd, who would become the first American astronaut in space, dubbed the machine the “Vomit Comet” and bailed out early in his first attempt on the MASTIF.

By all measures Cobb aced the tests. Lovelace was impressed and went public with the results at the 1960 Space and Naval Medicine Congress in Sweden.

“We are already in a position to say that certain qualities of the female space pilot are preferable to those of her male colleague,” he said in a statement that caught NASA and most of the world by surprise.

“There is no question but that women will eventually participate in space flight therefore we must have data on them comparable to what we have obtained on men.” He adde that he would be recruiting more women for testing.

Lovelace found 19 other women, mostly through the Ninety Nines, a women pilots’ organization that had been founded by Amelia Earhart. After two stages of testing, 13 of them, including Cobbs and Funk would pass, doing well enough to advance to the most grueling and final stage. That would take place at the U.S. Naval School of Medicine in Pensacola, Florida and in order for the women to use the facilities, NASA had to give permission. They said no.

Even though Cobb had been appointed a NASA consultant, the agency apparently never had plans to integrate women into the Mercury 7. By now, three American men from that group had gone into space and the program was on a steady track. To bring women into the program would setback their timetable. That’s what NASA said publicly. But in reality, at a time when few women had careers and the kinds of opportunities that were yet to come in the next decades, NASA and the country were unable to wrap their head around the idea of female astronauts. And so with that, the Mercury 13 was finished, a crash landing for a program that was bold and ambitious far beyond its time.

Cobb and fellow FLAT Jane Briggs Hart, whose husband was Michigan senator Tom Hart, went to Washington to lobby government officials for support to continue the testing. They succeeded in getting a Congressional hearing. Astronauts John Glenn and Scott Carpenter, now heroes from their flights into space, testified.

Jane Briggs Hart (right), one of the 13 First Lady Astronaut Trainees,

with Jerrie Cobb

“The men go off and fight the wars and fly the airplanes and come back and help design and build and test them,” Glenn declared. “The fact that women are not in this field is a fact of our social order. It may be undesirable.”

Adding the final nail in the WIS coffin, he went on to say, “…to spend many millions of dollars to additionally qualify other people whom we don’t particularly need, regardless of sex, creed or color, doesn’t seem right, when we already have these qualified people.”

It wouldn’t be until 1978 that NASA would include the first women in its official astronaut corps. Those trailblazers were Anna Fisher, Shannon Lucid, Judith Resnick, Sally Ride, Margaret Seddon and Kathryn Sullivan.

The women of the Mercury were stunned, their dreams of going into space destroyed. But all of them continued to fly. In 1965, Jerrie Cobb bought a small twin engine plane and began flying humanitarian missions, delivering doctors, food and medicines to indigenous tribes in South America. In 1980, she was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Wally Funk applied twice to NASA to be part of its Gemini class of astronauts but was rejected. She went on to be the first woman inspector for the Federal Aviation Administration and one of the first women investigators for the National Transportation Safety Board.

Her astronaut dreams never died. When the first commercial space ventures began in the 1990s, Funk began trying to buy or train to become a civilian astronaut. Her efforts paid off when she was invited to take a seat on the first crewed flight of the Blue Origin rocket in 2021.

© Alice Look 2025

Executive Producer, The Remarkable Women Project