Louise and Ida Cook : Humanitarians

Using their love of opera as a cover, the Cook sisters risked their lives to rescue Jews from Nazi Germany.

To the world, Louise and Ida Cook were sisters who led quiet and unremarkable lives in 1930s London. With their unsophisticated demeanor and no-frills clothes from Marks and Spencer neither attracted much attention as clerk typists for the British Civil Service.

Ida and Louise Cook in their twenties

But under the surface, the sisters were daring humanitarians. In the years leading to World War II, they rescued 29 Jewish families from Germany as the Nazis’ rose to power. Working alone, without the knowledge or support of the British government or an international agency, they risked their lives traveling to Germany to meet with members of the resistance and refugees. They smuggled out valuables belonging to these refugees and upon returning to London, sold them, using the money for financial pledges to support their immigration to Britain.

With their own funds, they traveled as “nervous British spinsters” and fanatical opera fans attending performances in Vienna, Salzburg, Frankfurt, Munich and Berlin. Their trips were planned around their day jobs and done on weekends so they could be back at work on Monday mornings.

Among World War II’s unsung heroines, Louise and Ida Cook’s story may be the most ironic considering that opera provided the cover for their dangerous work. Underestimated as simple and quirky, no one ever suspected the sisters were capable of the undercover work they were doing.

And why would they? Their daily routine had been the same for years. Since completing secondary or high school - Louise in 1918 and Ida in 1921 – they had continued living with their parents and younger brothers in a modest flat in the Battersea part of London. Louise, born Mary Louise on June 19, 1901, was the older, more reserved sister; Ida, younger by three years, was born on August 24, 1904. Like most young women of their time, they did not go to college. On weekdays, the sisters took the Tube downtown to their jobs. When the workday ended, they came home and rarely went out for pleasure.

Neither sister had a boyfriend or suitor. World War I had taken the lives of 800,000 British men – six percent of the male population, dubbed “The Lost Generation.” The 1921 census had identified 1.72 million more women than men in this age group. Louise and Ida were part of this “Surplus Two Million” demographic. With no wealth and their plain looks, marriage prospects were slim.

In the aftermath of the war, there was a complete reversal of centuries of restrictions. Told that their chances of a husband and family were one in ten, young women like Louise and Ida were now encouraged to work, have careers and be independent. For Britain, it was a case of economic survival as the country struggled to recover from a devastating war with a decimated male population.

As grim as it might have sounded, it was also a recognition of the importance of women to the rebuilding of the country. And among the unexpected benefits were more opportunity and freedom for British women, including the hard-fought right to vote, passed into law in 1928.

In 1923, the sisters’ mundane world was turned upside down when Louise, 22 and Ida,19, discovered opera. Their fascination began one day when Louise wandered into a music lecture during her lunch hour at work. An hour later, she was “slightly dazed,” as she described it and hooked on the music. She immediately decided she wanted – no needed - to buy a gramophone and records, putting down a deposit toward the purchase which would cost $2200 today. On her small government salary, this would mean months of forgoing lunches, Tube fares and other small treats.

The sisters had always been close and it wasn’t long before Ida became an opera fan too. Louise and Ida not only fell in love with opera but became, according to their nephew, John Cook, “opera groupies.” Ida, who was more creative, would whip up evening outfits using patterns found in magazines so they could attend performances in style. They wrote fan mail to their favorite stars, queued for the cheapest seats for shows at Covent Garden and became regulars at the stage doors of Royal Albert Hall, waiting to get autographs and glimpses of the divas and divos (male opera singers).

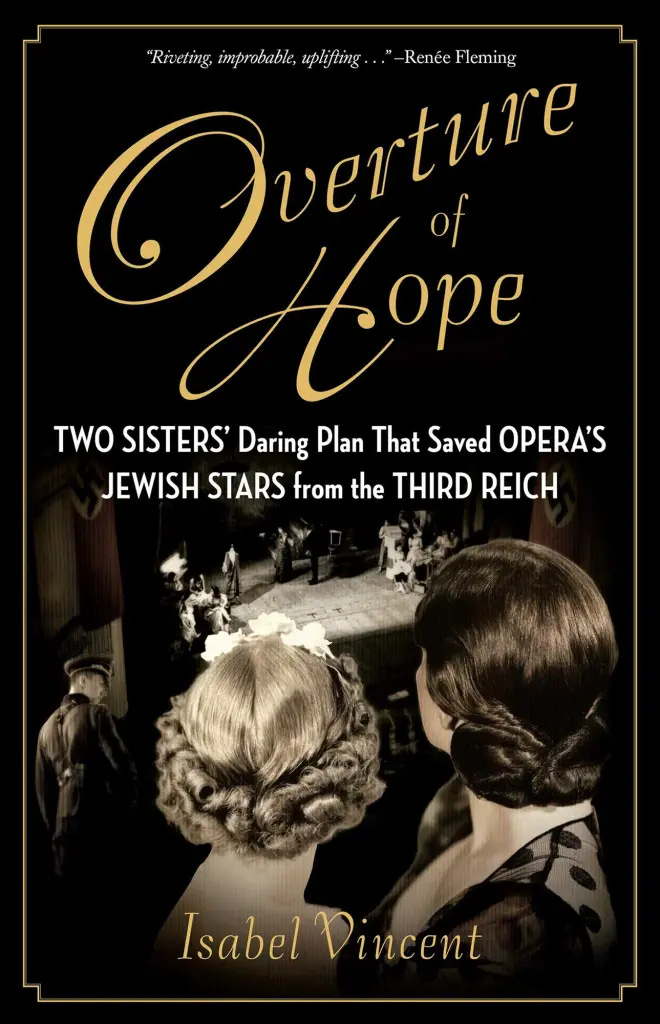

In 1926, after two years of scrimping for the cost of passage on an ocean liner and a hotel room in New York City, they followed one of their idols across the Atlantic to see her perform at the Metropolitan Opera House. That trip was the first time they had ever left the country. It was “an incredible accomplishment – a testament to their extraordinary strength of will…a harbinger of what was to come: together and determined, nothing would stop them,” author Isabel Vincent wrote in her book about the sisters, Overture to Hope.

But maintaining an opera-loving lifestyle was difficult on their modest salaries. Ida had done some freelance writing about their opera outings to supplement their income, but by 1935, twelve years into their obsession, the sisters were broke.

When Boon and Mills, a major romance novel publisher, offered Ida a contract in 1936, she jumped at the chance and quit her government job. Perhaps it was from absorbing the dramas of the operas she had seen, but Ida, it turned out, had a knack for writing pot boilers that became best sellers. Over the next fifty years, using the name of Mary Burchell, Ida penned 129 books. Soon, she was pulling in much more than her salary as a court typist. Louise played the role of silent editor and consultant, typing manuscripts, and providing ideas for plots and characters of Ida’s books.

The income from Ida Cook’s romance novels paid for the sisters’ refugee work.

With success, Ida and Louise no longer had to economize for their opera trips. At the same time, they were becoming aware of the “…the full horror of what was happening in Europe,” as Ida later wrote in her 1950 memoir The Bravest Voices.

Under Hitler, Germany had enacted the Nuremberg Laws which legalized antisemitism in all parts of society. Jews were banned from working in government regulated professions including medicine and education, from owning businesses, attending schools and universities, marrying non-Jews, voting or holding office. Stripped of civil and political rights, many were publicly persecuted and violently harassed.

For Jews, staying in Germany was becoming impossible, but leaving was equally daunting. If they were able to find a country that would admit them, they were allowed to take only 10% of their financial assets on top of which was imposed a heavy immigration tax.

Refugees also had to meet immigration rules of the countries they were going to. Britain required a minimum of 50 British pounds, worth about $5000 today, be deposited in a bank account. In addition, children under 18 would only be allowed into the country if they were adopted; women could enter as maids or domestics if they had a confirmed job offer; and adult males needed to be sponsored by a British citizen and provide proof of further emigration to another country.

Despite their many trips to Austria and Germany, the Cooks had paid little attention to the Nazis. The sisters had “stumbled” into saving Jews, Ida admitted, but once aware they were fully committed. “We were simply moved by a sense of furious revolt against the brutality and injustice of it all,” she wrote in the memoir, “and (we) were willing to help any deserving case brought to our notice, to the best of our small capacity.”

In the beginning, most of the people Louise and Ida helped were connected to the opera world. Clemens Krauss, conductor of the Vienna Opera and later the Berlin and Munich Operas, and his soprano wife Viorica Ursuleac introduced the sisters to Mitia Mayer Lisman, an opera lecturer who was trying to get herself and her family out of Germany.

The fate of Lisman’s daughter, Elise, a 17-year-old music student was up in the air. With Louise and Ida’s help, she was able to leave. The sisters had recently rented an apartment in London’s Dolphin Square and Elise became its first occupant. The same flat would become a temporary landing pad for dozens more families through the war.

As word of mouth spread about the sisters’ work, opera became a secondary reason for their trips to Germany. Their cover story was that they were opera fans going to see their favorite stars perform. The sisters did go to the opera, but they spent more time meeting with refugees who pleaded their case for rescue.

“Louise began to learn German so that she could interview in German if necessary,” Ida wrote. “I financed the trips from the romantic novels – and very strange it was, switching from romantic fiction to tragic fact.”

Every few months, on a Friday evening, the sisters would catch the last flight to Cologne, Germany, leaving from London’s Croydon Airport. Arriving at 9:30 p.m., they would board the night train heading south for either Frankfurt or Munich.

The weekend was filled with meetings with refugees with an opera squeezed in on Saturday night. For the return home on Sunday evening, they altered their route to avoid running into the same border guards.

Often this involved a train ride to a port village in the Netherlands called the Hook of Holland. From there, they took a boat that sailed all night landing in Harwich, England the next morning. They’d catch a train for London and be at work – Louise at her desk on Whitehall Street and Ida at her typewriter at home -- on Monday morning.

The sisters “weren’t James Bond ladies,” as Ida put it, but they had the instincts of intelligence agents. They knew people – especially men – assumed they were slightly eccentric, perhaps even ditzy, music mad women so they played the image to their advantage. On trips to Germany, they dressed plainly and packed lightly, leaving plenty of room in their suitcases for the fancy clothes and valuables that refugees would give them to sell. The money they would raise from these sales would go toward the pledges required for them to be admitted to Britain.

Coming home with these actual jewels was a bit tricky but they had a strategy for that. They would often wear the biggest, most valuable necklace or fanciest pin on their simple outfits. They banked on the fact that people would assume these were fakes, probably from Woolworth’s. After all, how could these unsophisticated ladies afford pearls and real gold watches? In the case of fur coats, they were even more careful. Ripping off the original labels, they would sew on labels from British stores supplied to them by friends and supporters. The sisters were nothing if not clever.

In between their trips, they sought sponsors, filled out the paperwork, raised money by speaking about the Jewish refugee crisis at churches and local community groups. They were on a mission that would become as important to them as their love for opera.

Louise and Ida Cook made many trips crossing enemy lines until September 1939, when World War II broke out with Hitler’s invasion of Poland. With Britain and France at war now, the borders were closed and there were no more trips to Germany. Instead, Ida became a warden for one of the city’s bomb shelters. Louise was relocated to Wales with her job.

After the war ended, the sisters continued their humanitarian efforts. Ida and Louise volunteered for an international group to help displaced non-German refugees, raising funds and visiting camps where they were being temporarily housed. They resumed their love of opera, indulging in trips purely for pleasure. Ida continued turning out novels, becoming president of the Romantic Novelists Association in Britain in 1967.

And they began getting recognition for their valiant work. In 1965, they were given the distinction of Righteous Among Nations, the Israeli government’s highest honor for non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jewish people.

The sisters continued living together until they died; Ida from cancer in 1986 and Louise in 1991 from septicemia. In 2010, they were posthumously honored as “Heroes of the Holocaust” by the British government.

By Alice Look

© 2024 Alice Loo

k

Thanks for this, it made my morning!

Absolutely love this ❤️✨️⚘️