In the late 1880s, as the first wave of popular interest in astronomy took over the country, a group of women officially called The Harvard Computers caught the imagination of the public. In the days before calculators, laptops and smart phones – the term “computers” was the job description for people who were good at math and calculating figures and numbers.

At a time when women didn’t have professional careers and modern astronomy was still a mystery, many people didn’t take the Harvard Computers seriously. Newspapers referred to them in outrageously sexist terms, calling them “Pickering’s Girls” and “Pickering’s Harem.” While most of the group of about 80 women performed clerical tasks, several became trailblazers of a new field, creating standards and establishing processes for scientific stargazing.

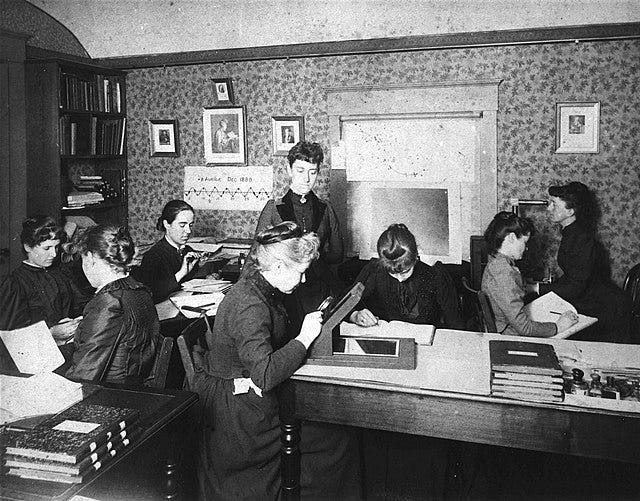

The Harvard Computers with Edward Pickering, circa 1913.

Williamina Fleming, Antonia Maury and Annie Jump Cannon were among the brightest stars in this remarkable galaxy of female scientists. They made original discoveries of stars, novae and nebulae and created systems for cataloging, identifying and explaining them, creating foundations on which additional discoveries could be made. Astrophysicists today still use the Harvard System of Spectral Classification, which was first developed by Cannon in 1901.

Some Harvard Computers were well educated and were among the first graduates of newly formed all-female colleges. Several had science degrees. Having pierced the “classroom ceiling” of the era, they were living examples that countered an absurd but common belief – promoted by scientists themselves – that women were too frail to handle the “stress” of education.

In his 1873 book, Sex in Education, Dr. Edward Clarke argued that “a woman’s body could only handle a limited number of developmental tasks at one time—that girls who spent too much energy developing their minds during puberty would end up with undeveloped or diseased reproductive systems.”

Fortunately, there were men who didn’t share that view, at least not entirely. Among them was the director of the Harvard College Observatory (HCO), Edward Charles Pickering, a physicist whose mission was to create a catalog and map of the stars in the sky – very ambitious challenge that would later become the Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra.

For centuries, astronomers had relied on their eyes to record and identify stars visible in the night skies. Pickering elevated the research to a more scientific and reliable level by using photometry and spectroscopy to record permanent images of the stars. In spectroscopy, prisms placed in front of the telescope’s lens split the light into a spectrum, which is analyzed for a star’s light, temperature and chemical composition.

Pickering hired a staff of male worker bees to study thousands of glass plate photographs taken through the observatory telescope. Not only was the work complex, precise and tedious, but there was also a massive number of photographs and information to process.

Pickering knew the work would be slow, but a few years into the project he became worried about the quality of the work, especially the sloppy work habits of his chief assistant. Disgusted, Pickering fired him, declaring “even my maid could do a better job.”

Even though his comment played into another common stereotype - that women were not the intellectual equals of men – Pickering proved to be right, because his maid did indeed do a better job.

Williamina Fleming was Pickering’s maid before she became a Harvard Computer.

Williamina Fleming was a 23-year-old recent immigrant from Dundee, Scotland who met Pickering and his wife, Elizabeth in 1879 when she took a job as their parlor maid.

Despite her age, Fleming, born Williamina Paton Stevens on May 15, 1857, was no stranger to adversity and resilience. When she was seven, her father died, turning his wife into a single mother of nine children. By 14, according to Harvard Magazine, Stevens was student-teaching part-time to help support the family.

At 20, she married James Fleming, a banker and widower 16 years older, counting no doubt on a life of comfortable stability. However, the following year, in 1878, the couple boarded a ship headed for America. Soon after arriving in Boston, Fleming’s husband left her. Pregnant, Fleming had no choice but to find employment on her own.

Impressed by her lively spirit and quick intellect, Pickering gave Fleming a part-time try-out and found she was much more valuable to him at the Observatory than dusting furniture in his home. She was hired as the first Computer in 1881, proving to be so competent that within five years, she was promoted. In her new role, she oversaw the entire group of Computers and soon began hiring more women to keep up with the demands of the work.

Edward Pickering might have supported some feminist ideas but hiring women also had economic benefits for him. Almost a hundred years before the idea of equal pay became law, employers could legally hire men and women for the same job and pay them different salaries.

At the Observatory, women were paid 25-50 cents an hour while men could make more than a dollar an hour. It was a fact that irked Fleming, a single mother. “I am immediately told that I receive an excellent salary as women’s salaries stand.…” she wrote in her journal which is now in the Harvard archives. “Does he (Pickering) ever think that I have a home to keep and a family to take care of as well as the men…And this is considered an enlightened age!”

In black and white photos taken of the group, the work of the Harvard Computers did not look demanding. But it was. The work week was six days and the women worked in tight quarters, almost elbow to elbow and often in pairs. One woman used a magnifying glass to scrutinize a heavy glass plate on which there were many dots, each one representing a star.

The women worked for pennies an hour, similar to the going rate for factory workers.

As she counted them, she would assess each one for their luminosity, size and other properties, following the standards of the Pickering-Fleming system – a classification scheme Pickering and Fleming had developed. Her partner would enter the information into a large notebook. Other women would compare the photos and classify them. It was exciting at first but quickly became a grind when neck and eye strain kicked in.

Using this system, Fleming herself catalogued more than 10,000 stars over the length of her career. She is also credited with discovering 300 variable stars, ten novae and 59 nebulae, including the Horsehead Nebula in 1888, one of the most distinctive and brightest stellar objects in the sky.

In 1899, she was the first woman named Curator of Astronomical Photographs at Harvard. A greater recognition came in 1906 when she became the first female honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society. Even at the end of her career, there was no flagging of energy. In 1910, a year before her death, she published her findings on white dwarfs, those huge, dense, dying stars that she had been among the first to discover.

One of the most significant hires that Fleming made was Antonia Maury (born March 21, 1866), a brilliant young scientist who had graduated from Vassar with honors in physics, astronomy and philosophy.

Maury was the niece of astronomer Henry Draper, whose brainchild was the very catalogue of stars the Computers were compiling. She arrived at the Observatory in 1887 with ideas on how to finetune the Pickering-Fleming classification system to gather more information about stars. But the environment at Harvard did not encourage the same kind of independent thinking she had found at Vassar and Maury’s annoyed boss rejected her ideas. Little did Edward Pickering know that decades later, in 1922, Maury’s ideas would be incorporated into the International Astronomical Association’s star classification system.

In 1889, while investigating the stars in the northern hemisphere, Maury made an exciting discovery of Beta Aurigae, a spectroscopic binary or double star. She calculated its orbit and researched its properties as well as that of another double star that Pickering had discovered, called Zeta Ursae Majoris. At a National Academy of Sciences meeting later that year, outside of a brief mention of a “Miss A. C. Maury,” Pickering took credit for her findings.

After this second incident, Maury knew that the Observatory was not the place for her. She quit in 1891, but never completely severed all ties. As the leading astronomical research center in America, the HCO was producing groundbreaking work. Maury returned in 1893, to complete the research she had started with a promise from Pickering that she would get credit for her work.

In 1897, after studying 4800 photographs of more than 680 stars, Maury was listed as the author on the first research paper ever published by a woman in the Annals of the Harvard College Observatory.

Maury went on to teach physics and chemistry at a private high school for girls for two decades and then became an adjunct professor at Harvard in 1918.

Maury was much more than a Harvard Computer. In a 2016 Time article, Yale astronomer and historian Dorrit Hoffleit wrote, “All of the other women who achieved greatness at Harvard were doing what Pickering wanted them to. It was only Miss Maury who was the independent renegade, and she couldn’t have been that if she hadn’t had an important family background, either.”

Annie Jump Cannon (born December 11, 1863) was another pioneering astronomer who arrived at the Observatory in1896. Cannon’s fascination with the stars began as a childhood pastime when her mother began taking her to the roof of their Delaware home to teach her the constellations. Later, with her mother’s encouragement, she attended Wellesley College, studying physics and astronomy with Sarah Whiting, a professor who had been mentored by Edward Pickering. Later, as a graduate student, she enrolled in classes at Radcliffe, Harvard’s “sister” school in order to gain access to the HCO telescope.

Annie Jump Cannon spent more than 40 years at the Harvard Observatory.

Cannon’s background made her well equipped for the work at the Observatory. With her trained eyes, she was able to accurately identify three stars a minute and up to 5,000 a month. Over her lengthy career at the HCO, Cannon became known as “the census taker of the sky,” for identifying more than 350,000 stars.

Cannon’s other lasting contribution to the HCO and the field of astronomy is her revision of the star classification system that Pickering and Fleming had originated. She re-shuffled the categories into an alphabetic scheme of O B A F G K M to link color together with temperature in classifying the hottest to coolest stars. This system became official Harvard System of Spectral Classification, still used by astronomers today. And in 1922, the International Astronomical Association added it as one of its systems for stellar identification.

Cannon never let her disability as a deaf person interfere with her career and life. She was also a suffragist and feminist who advocated for women in science.

Among many honors, she was the first woman to receive an honorary degree from Oxford and the first woman elected as an officer to the American Astronomical Society. Using the money from one of the awards she would win, she endowed the Annie Jump Cannon Award which the Society continues to give today to an outstanding young woman astronomer. Despite the numerous recognitions, Harvard refused to give her a permanent faculty position until 1938, three years before she died.

In addition to Fleming, Maury and Cannon, two other Computers of note were Henrietta Swan Leavitt and Cecilia Payne Gaposchkin. Leavitt’s pioneering work on calculating distances in space was used by Edwin Hubble to determine the existence of galaxies beyond the Milky Way and Gaposchkin’s research into the chemical composition of stars helped develop ideas about nuclear fusion.

©2024 Alice Look

Executive Producer, Remarkable Women Stories